Considerations in Designing the New Pediatric Digestive Health Outpatient Center

When Dr. Joel E. Lavine arrived (in 2010) as the Division Chief for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at New York Presbyterian Hospital and the Columbia College of Medicine, he encountered several obstacles that precluded the Division from achieving the potential expected in a premier medical center in the middle of the largest metropolis in the United States. The Division did not have its own outpatient space to see patients, utilizing Pulmonary Division space when they had vacancies. The endoscopy suite was only open three days a week, without dedicated staffing, which precluded faculty from having scheduled time to perform procedures. There was no triage room or staff, so each physician had to weigh, measure, and assess their patient’s vital signs. As well, all of the charts were on paper, requiring laborious filing and delivery of patient records.

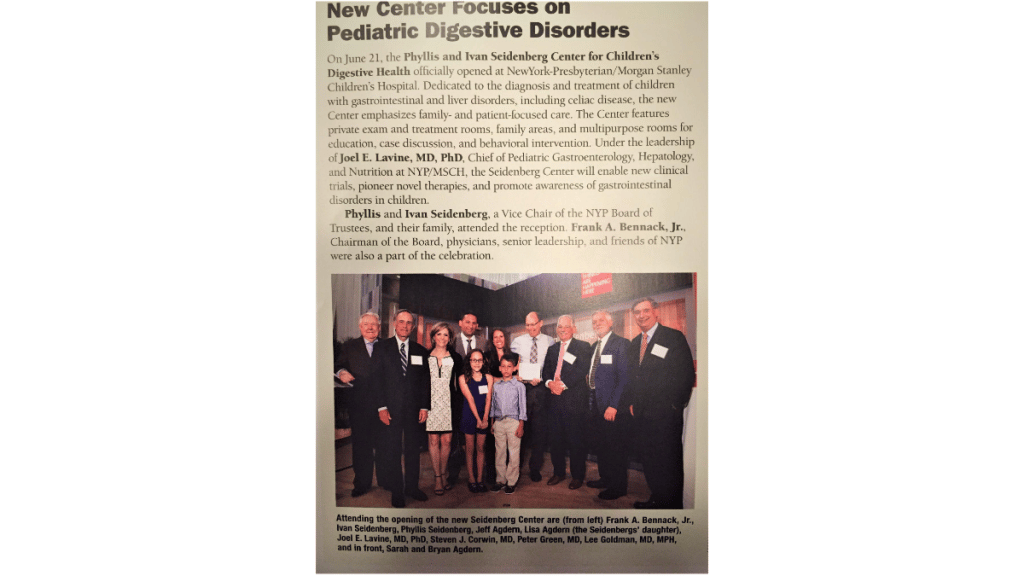

About a year after Joel Lavine’s arrival, he received a call from the CEO of NYP asking him to meet members of the Seidenberg family. After discussions surrounding the Division’s need for dedicated outpatient clinics and procedure space to become a premier center for pediatric digestive health, the Seidenberg family generously donated 15 million dollars to cultivate the Division into one of the premier centers in the world. The Seidenberg family and Dr. Lavine agreed that developing dedicated outpatient space for clinical care, procedures, and teaching would be paramount and that 2 million dollars of the total would support innovative research surrounding the spectrum of celiac disease.

Given this unprecedented opportunity – which was recognized in a widely attended ceremony to celebrate the family’s generosity – Dr. Joel Lavine set out to design a center that would become a template for capacity, functionality, appeal, and accessibility. With the 5000 square feet available, the Seidenberg Center first required a major infrastructure overhaul of the ventilation, plumbing, wiring, insulation, and architecture. All of the ceilings, walls, floors, windows, pipes, and doors were removed and replaced in an architectural reconfiguration that allowed 15 examination rooms, two dedicated consultation rooms, a large and comfortable waiting room, two triage rooms, ancillary offices for dietitians, social workers, and psychologists, and a conference room for lectures, family support groups, and conferencing between faculty and trainees. There was also an administrative intake and checkout space, a phlebotomy room, and a rear entry/exit to allow accessibility and privacy for those in wheelchairs or gurneys. A procedure room with surgical lighting, large enough to perform needed procedures, including motility assessments, and an “in suite” bathroom” to allow clean-outs needed for colonoscopy procedures. Finally, a room for patients to learn biofeedback (with computer software) to relieve functional abdominal pain, take surveys, or engage in specific research protocols was included.

Given that this space would be used for a multi-disciplinary facility for obesity care and bariatric surgery considerations, special toilets were installed that would hold up to the weight of some of these patients. Unique scales were installed to measure very large adolescents, and special exam tables and chairs that accommodated the size of these adolescents were put in designated rooms.

Each examination room needed to be designed for safety assurance. As this was a pediatric facility, sharps containers and certain supplies must be kept out of reach. Doors did not open into the hallway. Linen and trash had to be in areas accessible to staff but not patients. Otoscopes and ophthalmoscopes needed to be near the exam table but out of reach of younger children. Computer monitors and keyboards were placed so that providers would face parents and patients while inputting data. Electrical outlets were placed in areas inaccessible to children. Lastly, wall space needed to remain uncluttered in areas where pictures were hung, with each room having a different theme variation.

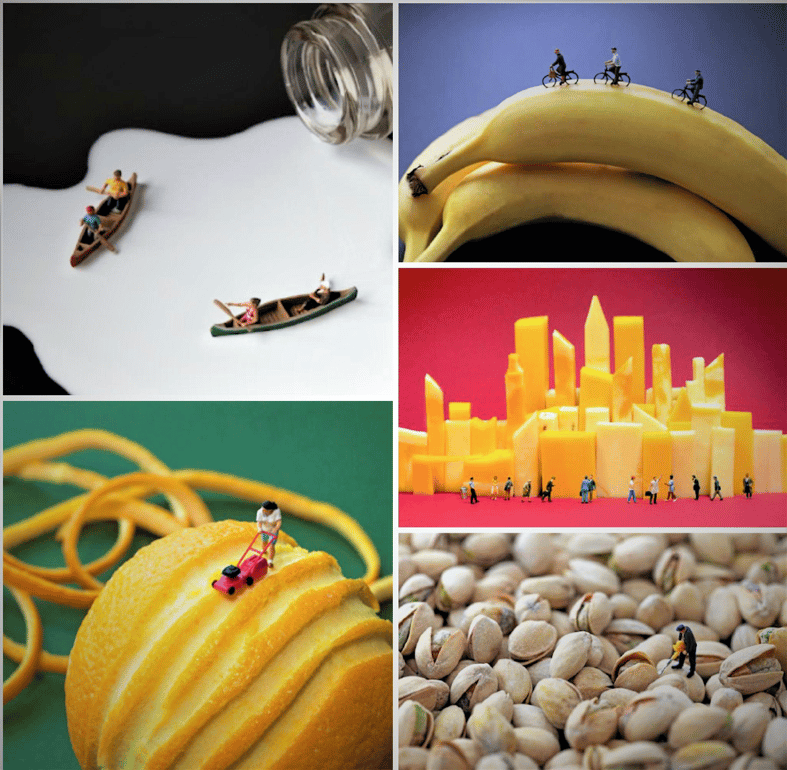

Dr. Joel Lavine took great care with the Center’s aesthetics. He did not want to use the primary colors often used in kindergartens and pediatric facilities and wanted the artwork in the halls and exam rooms to be interesting to both patients and their parents.

On a family trip to the Hamptons, Dr. Lavine found the artist he had been looking for. Each unique piece chosen for each room deals with a fanciful concept of people interacting with food. All of these selected works of art were created by Christopher Boffoli and only depicted healthy foods. Essentially every family that leaves an exam room comments on the artwork, and most ask to see what art is found in other rooms that may be vacant. Such art includes canoers rowing in spilled milk from a tipped-over bottle, professionals waiting for transportation in front of a Manhattan skyline constructed of cheese, or workers mowing the rind off of an orange, for example.

To this day, administrators and health providers from near and far come to see the layout, design, and art that make the Phyllis and Ivan Seidenberg Center for Children’s Digestive Health the premier outpatient space for functionality and whimsy in the United States.

Photo credits: Christopher Boffoli https://www.bigappetites.net